“Great-great-grandfather John stole three chickens to feed his family and was sent to Van Diemen’s Land for 14 years.”

This was the only story I knew about my convict ancestors. During my childhood the story rarely surfaced, but when it did it was always told from a victimhood perspective that Tasmanians relish.

While John was charged with stealing three chickens, there was more to the story. Later, once I began to investigate my family’s history, I learned that he was sent to Van Diemen’s Land because he was a serial law breaker who maraudered around Hertfordshire in the 1830s. The chicken case was just what brought him undone.

Stealing chickens, running scams and bragging about his drinking exploits were unlikely to be conversations starters at after-service gatherings of the Methodist Church in Sassafras during the mid 1860s. I suspect it was better ‘to just forget about all that’ and concentrate on the here, now, and hereafter.

The stony silence about the past would have been very ‘loud’ indeed. If anything was raised about growing up in Hertfordshire it would have been about the difficulties of living in extreme poverty and how much better it was in Sassafras. On a mischievous note, I wonder what discussions or jokes might have been shared with friends of similar background at the back of the church. Did the boy from Digswell escape his past?

Digswell days

The Ewingtons lived at Digswell, a hamlet of Hertfordshire. Within walking distance of the main town of Welwyn, which is about 40km north of central London. Currently connected by a fast train from Digswell Station to Liverpool Street Station, a daily commute to work at inner London would not have been in the Ewington family’s wildest dream. They were a classically big country clan, tied to the land.

I doubt the Ewingtons had much interest in or understanding of the momentous events in English history that happened in Hertfordshire .They unlikely knew they lived on land that was in the direct path of Roman invaders of 54 and 55 AD. I doubt they had any knowledge the first draft of the Magna Carta was written in nearby St Alban’s Abby in 1213, nor would they have cared that St Albans was ransacked by Henry VIII in the 1530s. That Elizabeth I held parliamentary sessions in Hertford Castle in 1564 and 1581 had no bearing on their daily lives. More recent times were more relevant. The Industrial Revolution, wars with France, and changes to property laws caused major social upheavals. The divide between rich and poor was extreme. Unemployment, poverty, and substandard living conditions were the norm for many families, including the Ewingtons. Drunkenness and crime were prevalent.

Newspaper Reports

Reports in the Hertford and Mercury Reformer gives occasional insight into the plight of the Ewingtons. Mary Ann Ewington was one of John’s seventeen – yes seventeen! – brothers and sisters. Described as a sickly and attenuated creature, she took James Wilmot, himself characterized as bad-tempered and half civilized, to court for the collection of alimony. Wilmot did not deny he was the father of Mary Ann’s child but tried to avoid payment. His defence was ‘he was led on by an utterly shameless and immoral person’[1]. Mary Ann won the case, but it is not known if Wilmot actually paid up. A few years later the Hertford and Mercury Reformer described how a Ewington female from Digswell, no Christian name mentioned, suffered sun stroke so badly while working in the fields she collapsed and did not recover.[2] Taken in isolation we could discount these as isolated incidents, but I think they are the tip of an experiential iceberg. These are stray hints of the desperate conditions in which the Ewingtons of Hertfordshire lived. They were short of money, and literally dropped through hard graft. No wonder they resorted to crime.

The Ewingtons spent a lot of time in pubs, a fact revealed by another fact: they were clearly involved in petty to serious crimes often enough to make the papers. They were defendants in cases ranging across petty theft, breaking and entering, being drunk and disorderly. On the other hand, they were plaintiffs in cases of theft and collection of alimony. They appeared in courts in at least the following towns of Hertfordshire: Digswell, Welwyn, Datchford, Monkten Hadley and St Albans. To be blunt they spent a lot of time drinking, stealing, and poaching animals. In short, John grew up in a community very far from the Methodist ideal.

At least five Ewingtons were banished to the antipodes as convicts. This enforced exodus included Joseph -most likely John’s father – in 1837, as well as John himself in 1838. The difference in destinies of these two men was stark. While John landed on his feet, became a respected farmer, married, and raised a large respectable family, Joseph was ground down by the brutality of the convict system.He could not adjust to his new world and ends up an old lag who just fades from recorded history.

But Joseph sowed the seeds of his own destiny. 5’5’’(162cm) tall and of fair complexion, Joseph was a part time farm labourer[3] when he married Sarah Brothers at Digswell in 1809. The first of their seventeen children, James, was born the next year, and sixteen more until their last, Rebecca, was born in 1837, the year of Joseph’s conviction.

By then the Ewingtons were struggling to make ends meet, a fact exacerbated by an ever-increasing number of mouths to feed. Seemingly to supplement the family’s income, Joseph took to petty theft. Success bred boldness, and he was soon running all manner of scams which become more and more daring. He was caught and punished on numerous occasions, with fines and spells in gaol, but he may have calculated that this was part of the game.

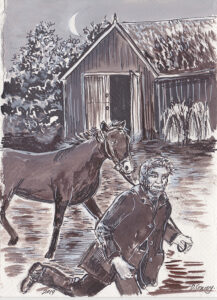

In 1837 a brazen and high-risk scam finally brought Joseph undone. One night Joseph stole a pony from William Horn to whom he had sold the pony earlier that very day. Horn had Joseph arrested. Joseph’s defence was he bought the horse to sell it on at a profit. The magistrate was not convinced. Believing that Joseph was running contrived schemes, the magistrate found Joseph guilty of horse stealing and sentenced him to 10 years transportation. Joseph arrived in Van Diemen’s Land onboard the Coromandel on 26th of October 1838

Van Dieman’s Land

But his ways stuck. Becoming a servant gardener for Mr. Archer, A large landowner near Westbury, Joseph appears to have continued running scams. He pilfered and illegally sold Archer’s vegetables.

Archer has Joseph charged in 1851 for stealing peas and selling them to Mr Hays a storekeeper in Deloraine. Found guilty, Joseph was sent to the Cascaded Workstation for 18 months with hard labour. Even for the times this was a hefty sentence. I suspect he had been running scams for some time. By now he was in his early sixties, quite old for the times so he may not have survived the sentence. If he did, he was a candidate to have gone bush ot get away from authority, and perhaps responsibilty. He passes from the record without any clear signs that he even crossed paths with his son.

Digswell

Joseph’s transportation had not deterred the Digswell Ewingtons from a life of crime. In 1838 at least six, some on multiple occasions, appeared before a magistrate. John was among them. Poaching animals was high on his agenda but he also spent a lot of time in and around hotels running various schemes. LIke father like son.

But John certainly continued to maintain dodgy company. John was directly involved with or an accessory to many incidents which were often in or nearby hotels that included brawling, threatening women, police and poaching. In the late 1830s he was clearly heading for serious trouble if his circumstances didn’t change, and in that respect his path to Van Diemen’s Land is unsurprising. After being found guilty of poaching he was sentenced to 14 years transportation.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court, 14th May 1838, page 25[7]

JOHN EWINGTON was indicted for stealing, on the 2nd of May, 3 fowls, price 4s. 6d.; the property of Samuel Strong; and that he had been before convicted of felony.

SAMUEL STRONG. I live at Monkton Hadley, Middlesex [about 20 km away from Digswell], and have a small farm. On Wednesday night, the 2nd of May, my fowls were locked up—on the 3rd of May I missed eight fowls, three of which have been recovered—I saw them before the Magistrate and know them to be mine—the prisoner was a stranger.

JOHN PESTILL . I live with Mr. Strong. On the 2nd of May I put the fowls into the hen-roost and locked the door, which is in the yard—I went there again about half-past five o’clock in the morning, and found the door broken open, and missed eight fowls—the policeman showed me three afterwards, which I know to be master’s—the rest are lost—I do not know the prisoner.

JOHN WAKENELL . I am a policeman. I fell in with the prisoner on the 3rd of May, at Whetstone, about two and a half miles from the prosecutor’s, about three o’clock in the morning—he had something under his clothes—I asked what it was—he said he had nothing—I said he had—he then said it was victuals—I wished him to show it me—he felt his clothes, and said he could not get it out—I said” I must have it out”—a scuffle ensued, and we both fell to the ground—he bit my hand, and at last I lost my hold, and he ran away with a large stick which I carry—when I came near him he swore he would knock me down, and gave me a tremendous blow on the head—I closed on him, and struggled with him—I called a wagoner to my assistance, but when he came the prisoner knew him, and he endeavoured to get him from me, but another person came up and assisted me—I took him to the station-house, and ongoing back, found two fowls where we had been scuttling, and one I found in his pocket—they were warm, as if recently killed—he whispered to the wagoner, and called him by his name—I snowed the fowls to Pestill.

HENRY BAILEY . I assisted Wakenell in handcuffing the prisoner, as he resisted.

THOMAS AUSTIN. I am a policeman. I went to Mr. Strong’s premises with the prisoner’s shoes, and compared them with footmarks about eight yards from the premises—they tallied in all respects.

Prisoner. He said there were more nails in my shoes than in the marks. Witness. There were no nails in them—they corresponded exactly—the nails had been worn out.

Prisoner’s Defence. I was going to Highgate that morning, and at the bottom of the hill I went behind a heap of gravel, and saw the fowls lying in a ditch—I picked them up—they felt warm—I put one into my pocket, and the other two inside my jacket, and buttoned it up.

JOHN LEGO . I am a turnkey of Hertford jail. I produce a certificate of the prisoner’s former conviction, which I obtained from the clerk of the peace—(read)—he is the man who was convicted.

GUILTY —Aged 21. Transported for Fourteen Years.

Before Mr. Justice Patteson.

Whenever I read this I feel sorry for John. He offered only a pathetic defence, and had learnt little from his own attempt at being a prosecutor. In my view this was more than opportunistic stealing. This was a premeditated crime. But why would he want to steal chickens? Given his record it is hard to know. Maybe it was to help feed the family or to fence them at the pub or both. Recalling Joseph had just been transported the plight of the family would have been in turmoil so perhaps there was a strong element of truth in the old family story. Even habitual criminals get hungry.

After sentence John was immediately sent to the Hulks. While following his father’s footsteps, this is where their lives started to diverge. John’s conduct report suggests he was much better behaved in custody. Then, while he was transported to Van Diemen’s Land on the Gilmore in 1839, he maintained what the surgeon’s report styled ‘good’ behavior.

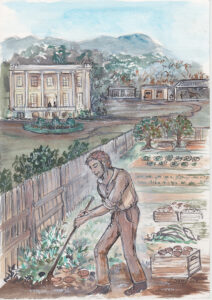

John was also lucky to have arrived at Clarendon in a time of peace. The Vandemonian War, which had effectively extirpated the Aboriginal population of Van Diemen’s Land, was safely in the past and rarely discussed in public. In fact, the property itself had grown comfortable and its owners prosperous in the peace. James Cox, the son of wealthy and well-connected William Cox of Sydney, had built Clarendon House between 1836 and 1838 with convict labour. John arrived when it was nearly complete and lived in the servant quarters located to the southeast of the main house.

John would have been aware Cox was a pioneer of Van Diemen’s Land and had become one of the largest and wealthiest landowners, owning more than 2000 hectares. It would have been obvious to John that Cox was very influential. Even as a convict servant John would have been aware of Cox’s leading role in the development of the sheep and beef industries. Further he would be aware Cox imported fallow deer for game hunting and was prominent in the racing industry. So, John was a convict servant to Cox who was coming to the height of his power with Clarendon a clear representation of it. A very lucky assignment indeed.

John may have heard Cox initially lived in Launceston as bushrangers made living at Morven too dangerous. I suspect John would hear romantic tales of marauding bushrangers and how the pioneers endured all manner of hardships. Bushrangers were largely subdued by the time John arrived. Living at Clarendon, as a convict servant, provided John towed the line, would have been quite safe. The exploits of bushrangers may even have been part of mealtime conversations. Whether the servants approached the Vandemonian War differently in conversation is hard to tell. I suspect it was seldom talked about, or at least parts of it were left unsaid. I wonder whether he heard much about Cox funding roving parties, led by his son, to ‘round up the blacks’ in the late 1820s and early 1830s[8].

Given John’s own backstory, I guess he was mostly glad of the security. Not so much from Aboriginal spears, but from the acute economic distress and social pressures of his childhood. His basic needs at least were being met in a way he could only dream of in Hertfordshire.