Jane Whitton

Towards Sassafras

Jane Whitton

When I first read Jane Whitton, my great, great, Grandmother’s convict record I thought she was incorrigible a ‘notorious strumpet and dangerous girl’. As I got to know her better however, I found my initial opinion a little self-righteous. I know think she was very clever, resourceful, knew what she wanted and used what was a brutal system to her own end.

I would have liked to have met Jane. I suspect however she would have left me in her wake as she moved from one idea to another. She was always on the go searching for a better life. George Shadbolt must have met her expectations or else this would not have been written.

The Formal Section

Introduction

Jane Whitton, my great, great, grandmother, born into poverty, was a feisty, somewhat racy young lady. Not only a ‘lady of the night’ she was also a bilker, relieving clients of their money and jewelry once she had them in a compromising position. A high-risk illegal occupation which resulted in her being convicted of theft and sent to Van Diemen’s Land. As a convict Jane endured all manner of hardships but was granted her freedom, married, and became a foundation member of a local church. The lady of the night had found salvation and become a pillar of a Christian community.

As Jane’s circumstances changed so did her behaviour. Once there was hope and opportunity, she took it. Any hint of discussions about her past after Sunday church services would have been met with stony silence.

England

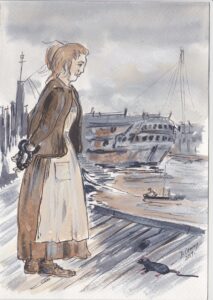

Born c. 1829, Jane was a slight woman. Her convict records put her at just 150 cm tall, with blue eyes and a fair complexion. She could read but it is doubtful she was able to write. Pockmarks suggested she suffered from smallpox at an early age. She grew up, as part of England’s underclass, at Litchford, a small town near Stafford in Central England. Jane was likely ‘on the town’ from a very young age. At age 17 she started working for and in conjunction with prostitute Hannah Miles, operating from a hotel in Porto Bello, a small village near Stafford. They got away with their scams for at least two years until they were arrested for stealing, two sovereigns, two half sovereigns, and a handkerchief from a client, John Butcher.

They conned Butcher to join them at a hotel on a promise of entertainment. Butcher somehow ended up in a state of undress and Jane and Hannah robbed him and ran off. Butcher chased them but was confronted by Jane and Hannah’s pimps, who were lurking outside the hotel. They had practiced this trick before.

But this time the patsy swallowed his pride and reported the incident to Constable Glover who was nearby. The police raided Miles’s house and considerable stolen property was found. Arrested, tried, and found guilty, the chairman of the jury described them as abandoned women connected to a gang of thieves and therefore dangerous to society. Even though it was their first offence they were transported for seven years.

Jane was transported on the Cadet departing Plymouth in November 1848 along with 149 other female convicts. John Bowman, the surgeon superintendent for the voyage, described her as ‘indifferent’. It was, at least, better than ‘bad’.

An attack of diarrhea lasting ten days had Bowman was concerned that Jane may have had a form of cholera. It must have been a miserable time, but more difficult times were ahead.

Van Diemen’s Land

Jane found herself in Ross, Cascades (Hobart), and Launceston Female Factories, which had similar operating procedures. After disembarking the Cadet she was sent to the Ross Female Factory making the journey either by foot or in a coach with a guard in 1850. On arrival she would have been made to take a bath, most likely had her head shaved, and issued with a jacket, a pair of stockings, shoes, a cap, a shift, a handkerchief, a petticoat, and an apron. New arrivals started in the crime class ward. Mothers were assigned to the nursery. Inmates had to earn the right to the pass holder ward.

As a crime class inmate, Jane worked twelve-hour days producing spun wool and flax, sewing, stocking knitting and straw plaiting was her new life. Small misdemeanors resulted in hard labour either, rock breaking or picking oakum. I suspect Jane found it almost impossible not to cross the line. She was sentenced to a total of 11 months of hard labour.

All female factories had hardened inmates who set up their own power relationships within the factory. Jane negotiated not only the official rules and regulations but also the unofficial ones of the inmates. Older more hardened inmates, known as the Flash Mob, preyed on younger less experienced inmates often resorting to thuggery to get what they wanted. Still, some female convicts, Jane included, preferred the overcrowded factories to private domestic work, often on isolated properties. It may have been less treacherous in the factories than negotiating the unwanted advances of settlers and their workers.

Jane spent most of her time in the Cascades Female Factory, the largest in Van Diemen’s Land. It was opened in 1828 with one yard. Two further punishment yards were added in 1832 and 1845 respectively. Yard 4, a Nursery Yard was built in 1850 just before Jane arrived. I imagine Jane had to constantly cover her back from guards and inmates, navigating official and unofficial rules.

Assignment

After surviving two years of brutality in the Female Factories, Jane was available for assignment. Between April 1852 and August 1853, she was assigned four times. Assignment was a lottery and there were winners and losers.

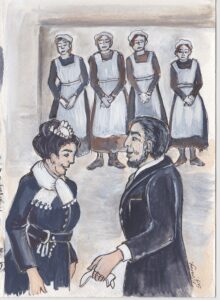

On the day of assignment Jane would have been lined up with ten or so other women in two rows facing one another. A male landowner would then walk between Jane and the other females. There was no discussion. If Jane was selected a handkerchief was dropped in front of her. Jane then picked it up and off she would go with the landowner. She had no idea of the character of the people, where she was going, or what the environment was like into which she was moving.

If Jane was assigned to a respectable and caring family, then she would have found conditions much like being a well-off servant in Britain with adequate clothing, food and shelter. Covering her back and being on the lookout, however, would always have been on her mind. There was still an imbalance of men and women in Van Diemen’s Land, and she would have been considered to be fair game. Recalling she lived ‘on the town’ for several years she had the where with all to learn and bend the rules to survive.

We do know however, by 1850 transportation was coming to an end and ‘respectable settlers’ were less likely to take on female convicts. Jane, therefore, was more likely assigned to a risky environment. From April 1852 until August 1853, she was assigned to four settlers. Each assignment lasted a short time before she was returned to a Female Factory. Initially I thought my great, great grandmother was incorrigible but on reflection she was playing the system to her advantage. If Jane did not like the assignment, she found a way to be returned to the Female Factories.

Marriage

Although Jane’s record was a little checkered, she was granted a ticket of leave in 1853. Things were looking up for Jane, but she continued to test the rules. Jane was on a mission to find a safe haven in a fiercely patriarchal society and considered marriage a way of achieving her goal. Hannah Miles, her partner in crime, was in a stable relationship and she was intent on doing the same. I suspect however, the partner needed to meet her expectations or else she would have found a way to move on.

In 1853 she described herself as free on an application to marry William Cooper in November 1853 resulting in 8 days of solitary confinement in the Launceston female factory. She persists and in May 1854 she was granted permission to marry George Shadbolt. They were married at the Independent Chappel, Green Ponds in July 1854. On June 26, 1855, she was declared free by servitude. Seven tumultuous years came to an end. The Shadbolts started their married life working for other people before moving to the North West Coast of Tasmania becoming the Shadbolts of Sassafras.

One Response

Jane certainly knew how to work the system, for her benefit