Towards Sassafras

The Shadbolts

Shadbolt derives from archery with variant spellings such as Shotboult or Shotbolt. Family legend states that the Shadbolts were bowmen who fought the Norman invaders in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. For centuries they were peasant farmers who plowed fields for tight-fisted absentee landlords.

The Shadbolts then, like the Ewingtons were part of the underclass of Hertfordshire, England. They lived at Datchworth just five kilometers from Digswell the home of the Ewingtons.

They lived by the proverb: He who does not steal from his masters steals from his children. Solomon, George, Benjamin, and Jonathon were inevitably caught and banished to the Antipodes a few years after the Ewingtons.

Their journey through the convict system was in stark contrast to John Ewington. They experienced the worst of Norfolk Island the world of Marcus Clark’s, For the Term of his Natural Life. Again, maybe my father was right. Another big dozer might be required.

They endured and survived the horrors of Norfolk Island and arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1846. From then on their stories are markedly different.

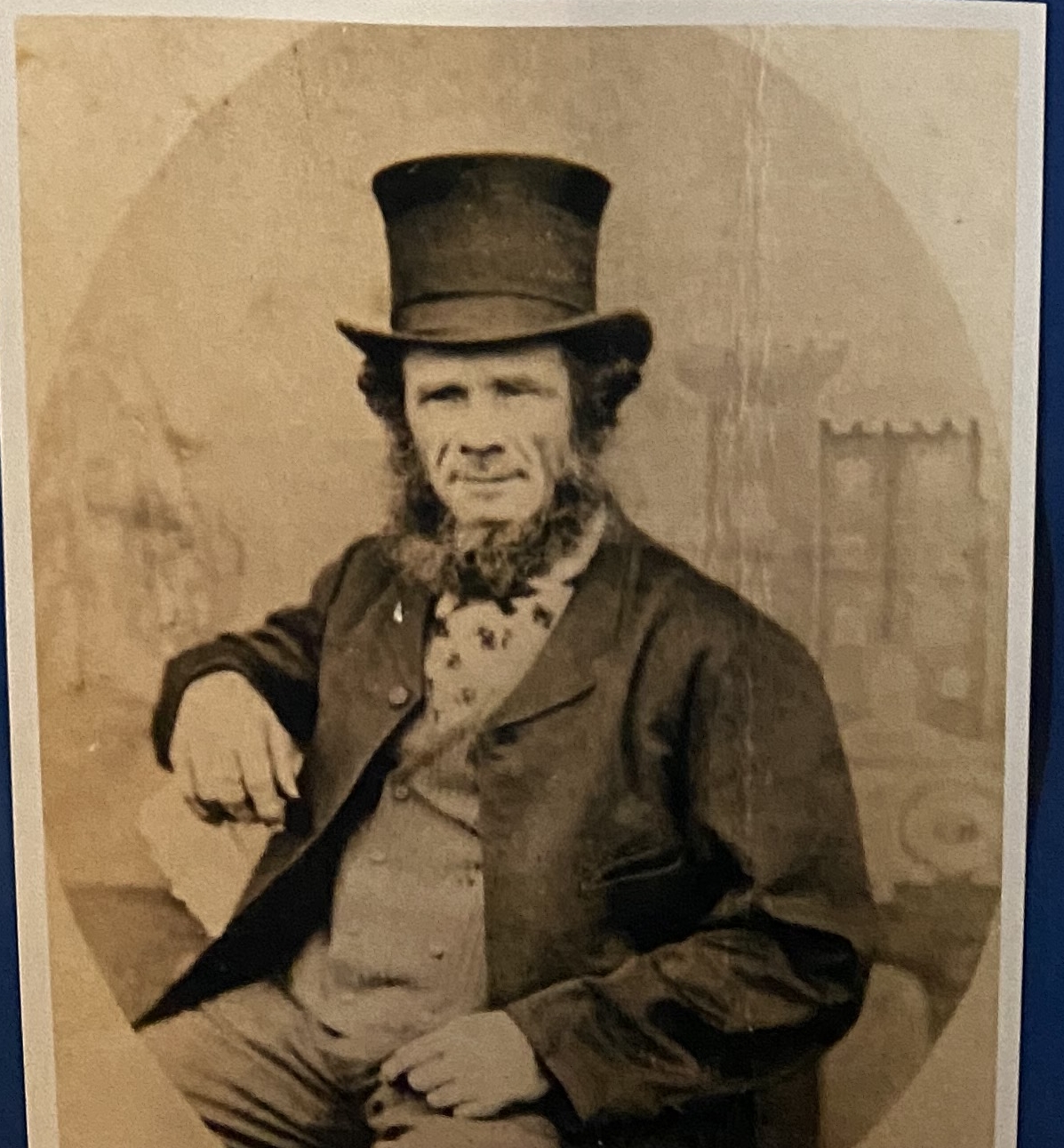

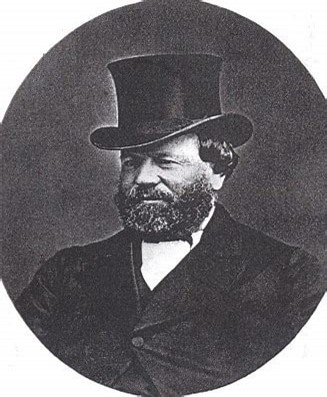

George Shadbolt – great-great-great-grandfather

Convict to a pillar of the community. He became a devout Methodist, successful businessman, and foundation member of the local church. He took a leading role in establishing a Sunday School and Government School.

Benjamin Shadbolt, George’s cousin and free settler of New Zealand. Well sort of.

After serving his sentence he continued to wheel and deal as a hawker, not always living within the law. Ends up at Port Arthur for a time. Migrates to New Zealand to make a fresh start. He became a successful, businessman, hotel owner, and racehorse owner who lived mostly within the law.

The Formal Section

Towards Sassafras – George Shadbolt

Introduction

Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania in 1856. There were celebrations across the island as Vandemonians became Tasmanians. A time for a new beginning and throw off the convict stain. Reverend John West started the movement against transportation in the early 1840s. He quickly garnered support from powerful people including James Cox of Clarendon Estate. Even though the likes of Cox built their estates on free convict labour, many considered it time to rid the state of the convict stain. Initially, support was not forthcoming from Britain however, so West campaigned across the island culminating with a meeting in Launceston in 1850 to seek co-operation from abolitionists across Australia. As a result, the Australian League for the Prevention of Transportation was formed in 1851. Momentum built resulting in Britain ending transportation to Van Diemen’s Land in 1853. A new name, Tasmania, was chosen to rid the name Van Diemen’s Land which would forever be associated with the convict stain.

But a class system as rigid as England was created and, we just don’t talk about that, became the norm. A fierce backlash set in, a backlash against remembrance, and against history itself. So strong was the backlash forgetting morphed into denial. In some families, children even abandoned their convict parents and other relations, denying their existence, for fear of being tainted with the convict stain. Ex-convicts were locked out of employment, social events and decision-making bodies. Denial and forgetting became necessary to succeed in such a class riddled society. This was the society the Shadbolt’s had to navigate. Forgetting and denial were evident in the Shadbolt’s story. Some succeeded in Tasmania, some left the state and succeeded, but for others it was all too difficult.

The Shadbolts

Linden Shadbolt conducted a successful blacksmiths business at Sassafras, Tasmania, in the early 1880s. According to Shadbolt family folklore his father, Benjamin Shadbolt, was a free settler of New Zealand. Benjamin, however, was also an ex-convict from Tasmania strongly encouraged to leave the state by his cousin George, also an ex-convict, or else he may well have spent the rest of his life in a Tasmanian prison. These details were lost over time. An example of Tasmanian selective memory and/or denial. The Shadbolts s were part of a den of thieves from Hertfordshire.

Shadbolts of Hertfordshire

In the early 1840s, as the anti-transportation movement was gaining ground in Van Diemen’s Land, the Shadbolts of Hertfordshire had a well-deserved reputation for burglary. They were a den of thieves who preyed on towns around Welywyn and knew the Ewingtons well. In fact, they were family. Solomon Shadbolt had married Eleonor Ewington. The Shadbolts were yet another part of England’s underclass, resorting to crime to survive.

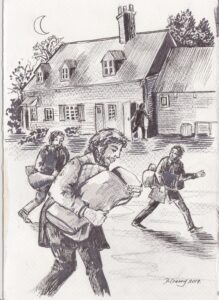

The den included at least my great, great, great grandfather Solomon his son great, great, grandfather George and cousins Benjamin and Jonathon, and were very active in the early 1840s. They had some narrow escapes before finally being caught for burglary in 1845.

In 1842 Jonathon and Benjamin were charged with attempted poaching from XXX. They violently assaulted Griffin, his gamekeeper, after he took their gun. They were found guilty and had to pay a substantial fine. The money was found from their female supporters who were at court as observers. They were however detained as Griffen pleaded he would not feel safe as the Shadbolts threatened revenge. The judge agreed and placed the Shadbolts on a good behavior bond with bail required before they could be released. Solomon Shadbolt and George Shadbolt, also at court, made representation to the judge that they could find the bail by tendering, a horse and cart, and furniture as surety. The judge accepted the surety and Jonathon and Benjamin were then free to go.

Griffen’s concern that the Shadbolts were bullies was confirmed in 1843. George Shadbolt was found guilty, and given a substantial fine, for threatening Anne Westwood. She gave evidence against Solomon Shadbolt for stealing a pig. Solomon was found guilty and jailed.

Later in 1843 Jonathon Shadbolt was charged with stealing hay. He allegedly hid the hay at Solomon Shadbolt’s residence who was charged with knowingly receiving stolen property. The case was dismissed when the judge discovered Solomon Shadbolt was in goal at the time of the offence. Clearly, the police were after the Shadbolts. This was however either very sloppy police work or fabrication of evidence but the Shadbolt’s days were numbered.

Trial Record

Eventually, the Shadbolt’s luck ran out, aided by some concerted police work. And, as the Hertfordshire Mercury’s account of their trial reveals, they now had few allies.

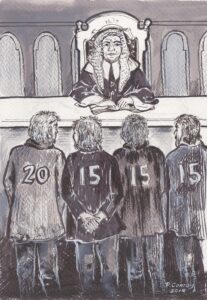

George Shadbolt, 25, Tewin, labourer, Benjamin Shadbolt, 20 Watton, Solomon 47, Tewin, Jonathon Shadbolt, 26, Watton.

3 February 1845 at Little Wymondley, broke and entered the dwelling house of Pricilla Blidell, widow, and stole therein a quantity of flannel, calico, and sundry pieces of money, and other articles, her property. One of the counts of indictment charge prisoner, Solomon Shadbolt, with having been previously convicted of felony. The Learned Judge, addressing the prisoners, said they had been convicted upon the clearest evidence, of an offence of a very aggravated character, that of burglary, which formally constituted a capital felony, attended by the forfeiture of life to those found guilty of it, — indeed many a criminal had paid the penalty of life for less of a crime than the one of which they stood convicted. There were no mitigating circumstances in their case, –and no one is coming forward to speak for their character, they merit the most severe punishment. The sentence against Solomon Shadbolt in consequence of his previous conviction, therefore, was that he be transported beyond the seas for the term of twenty years; and George Shadbolt, Benjamin Shadbolt, and Jonathon Shadbolt for 15 years. Too much praise cannot be given to the active and intelligent officers of Police engaged in the case. It is most satisfactory to know, that by the efficient manner in which the case was conducted for the prosecution the county has got rid of a family of notorious thieves, who have baffled the efforts of police for several years.

Journey to Norfolk Island

The Shadbolt men spent a short time on the hulks before being sent to Norfolk Island, a place with a reputation worse than Port Arthur. They arrived on board the Madya on 8 January 1846. I doubt my father was aware of this but after researching for this section I now have a greater appreciation of why he wanted to ‘forget about all that.’ Major Joseph Childs, a dull military hack distinguished only by his severity, was in charge when the Shadbolts arrived. He was replaced by John Giles Price, an even more sadistic ogre, who developed a psychopathological love hate relationship with prisoners. Childs and Price presided over a remote island prison, beyond any day-to-day supervision of their behaviour and played out their sadistic fantasies. As a result, prisoners rebelled and mutinied.

The Shadbolt’s journey to Norfolk Island was, on balance, relatively uneventful, bearing in mind they had never have been on ship before, Solomon, George and Benjamin left behind wives and children, and they were confined with over a hundred other prisoners. The journey however was the calm before the storm.

Norfolk Island

On arrival the Shadbolts were shown the penitentiary and then escorted to the beach to wash in the sea. Old hands rushed them while they were washing and plundered their possessions. The accompanying police could not or chose not to stop them. Welcome to Norfolk Island. Further at night if they didn’t stand up for themselves, they would have been preyed on by inmates picking locks, rushing them, beating them up and stealing possessions. There was no supervision in the penitentiary at night. The Shadbolts were hardened thieves who could fend for themselves, but this must have been a culture shock. Worse was to come.

The Shadbolts were fed food that was underweight, the grain foul, the meat of poorest quality, the maize-flour bread (known as ‘scrubbing -brushes’ for the inflammation its abrasive bran produced in the prisoners’ guts) scarcely edible. At least on arrival rations were distributed to individuals and some cooking was allowed. Even this privilege was withdrawn, and food was distributed on mass. Getting a fair share must have been a challenge but there were four of them. The food was prepared in, even for the times, sub-standard kitchens and inmates had to use fouled latrines. At the time of the Shadbolts arrival prisoners were simmering with mutinous resentment. Ophthalmia, gonorrhea and dysentery were endemic.

The Shadbolts survived a jail that was an unventilated pigsty, locked up with 800 prisoners every evening after work. The Shadbolts somehow navigated the after-lights-out subculture. What went on after lights out was no concern of the guards. The Shadbolts had to fend for themselves. They did not avoid secondary punishment with George, Jonathon and Benjamin sentenced to hard labour in chains.

Their conduct records indicated they navigated the subculture with some success, although it brought them grief. George was found in possession of 20lb (9kg) of mutton and put in chains for four months. Later he was sentenced to a chain gang for possessing a pipe and tobacco[. Jonathon and Benjamin were sentenced to hard labour for neglect of duty, which may have meant they looked or spoke to the guards the wrong way. George, Jonathon and Benjamin all spent time in the hospital. The record is silent on Solomon although he was a sick man on arrival suffering severe dysentery.

It seems George was the leader of the group. He successfully navigated the subculture to put himself in a position to steal, trade, or somehow acquire extra food and tobacco. Further I suspect he took the fall for the group. The system wore Solomon down, he was now 50, and I suspect the younger Shadbolts tried to protect him as best they could.

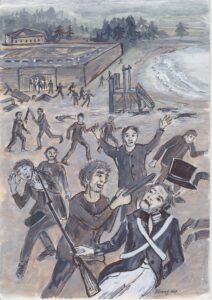

Cooking Pot Riot

The simmering discontent the Shadbolts felt on arrival came to a head after Childs ordered the confiscation of prisoners’ cooking equipment. In July 1846 prisoner disquiet and frustration turned to rage and rebellion resulting in the Cooking Pot Riot. The prisoners led by William Westwood, known as Jacky Jacky, stormed the cook house and stole cooking utensils including knives and axes. Within minutes hundreds of prisoners, including the Shadbolts, became a wild mob rushing about. There was no plan of action, it was a spontaneous uprising, and must have been a frightening spectacle. Four constables were murdered, and several were wounded before it was brought under control by the military. At least five convicts were killed, and several were wounded. The Shadbolts most likely observed the subsequent hanging of 12 of the ringleaders, in two groups of six, their bodies thrown into a pit near the pier.

Van Diemen’s Land

After surviving one of the most disgraceful chapters in British penal history the Shadbolts left Norfolk Island on Pestongee Bomangee in May 1847, for Van Diemen’s Land. There, their stories vary markedly.

Two departed the family scene relatively seamlessly. Solomon died at the Cascade Probation Station in January 1848. Perhaps the sheer brutality of the system was just too much. He was buried in an unmarked grave at the station. Jonathon left after reoffending, including by neglecting to respect private property and threatening to set fire to houses, he left a limited criminal paper trail. He was jailed on at least two occasions. But in the mid 1850s he went to Western Australia and disappeared from the record.

The other two, Benjamin and George, remained in close connection. Their stories, while very different, show how Tasmanians too easily misinterpret their Vandemonian past.

On the face of it, Benjamin did well. He was a servant on several properties around Campbell Town and Avoca between 1848 and 1852. He married a free settler’s daughter, Elizabeth Perran, and their first child Linden was born c. 1852. His only noteworthy misdemeanors were being absent without leave a couple of times. In 1852 he was granted a hawker licence, while still an assigned convict, and in 1854 was granted a ticket of leave.

But old habits of mind might have remained. Benjamin did okay for a while but his dubious sourcing of goods to hawk caused him major problems. He was accused of stealing a horse from John Ewington – yes great, great Grandfather John – at Deloraine. But because he could not positively identify the horse the case was dismissed.

However, Benjamin was not so lucky when charged with stealing 23 geese from the Bradens at Hagley on December 7, 1855. The Bradens were very clear about what happened and happy to identify the geese. Benjamin was found guilty and sent to Port Arthur for two years. This was just 24 days before Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania on January 1, 1856 .

After release, Benjamin was conditionally pardoned. But, while he was in prison, his cousin George effectively acted as Linden’s father.

Benjamin -Free Settler of New Zealand?

Once free Benjamin decided to make a fresh start somewhere else. Benjamin decided to migrate to New Zealand. He sailed on the Amasis leaving Hobart in March 1859, taking his pregnant wife Helen, Linden aged 7, Emma aged 4, and Amelia aged 2. But soon after leaving Tasmania the ship encountered rough weather and began to leak, forcing its return to Tasmania. Cousin George strongly encouraged Benjamin to make the move and family legend suggests George was disappointed when the ship returned with his cousin and family.

Benjamin persisted, however, and after the ship was repaired it sailed again, arriving safely in the Canterbury region of New Zealand in April 1859. But that branch of the Shadbolts arrived there without Linden. The young boy had been left behind with George. According to family tradition this was because he suffered terrible sea sickness on the first attempt. I doubt this was too much of a problem for Linden or George. George had acted as his father for up to four years, after all, so I suspect George thought it was a win-win to look after Linden and get rid of Benjamin.

The fresh start worked well for Benjamin, who became a successful boat owner, racehorse owner, farmer, and hotel proprietor. He left an estate of over 11 000 pounds and over four hundred people attended his funeral. A memorial poem concluded with the words ‘He wasn’t a saint. God bless him! We liked him better for that.’ Benjamin evidently found success by continuing to ‘wheel and deal,’ albeit now mostly within the law of his New Zealand home. But George took a different route to respectability. He found religion and became a born-again Methodist.

George Born-Again

Exactly when and how George was “born again” remains a little unclear. My hunch is it took place while George was on assignment to Captain James Dixon of Skelton Castle, Isis, which started in 1850. After several short-term assignments George remained with Dixon until he was pardoned. George even received a monetary allowance from Dixon. Dixon was associated with the Quakers and was a devout Christian. George was seemingly influenced by and attracted to the pious lifestyle.

George certainly seems to have found a less troubled path in life about this time, perhaps explaining why he was so keen to have a sea between himself and his wheeling and dealing cousin Benjamin. In 1852 George was granted a ticket of leave and in 1854 a conditional pardon. Shortly thereafter he married Jane Whitton and they became the Shadbolts of Sassafras. He was evidently settling down. Yet one piece of evidence really sticks out, affirming my sense that something significant happened to George in the early 1850s. In 1852 he donated two shillings to a fund-raising effort for an expedition to find previous governor John Franklin. Certainly, a charitable donation was something new in the documented parts of his life story. I suspect the thief from Hertfordshire would have had little interest in helping a governor. George certainly had come a long way.