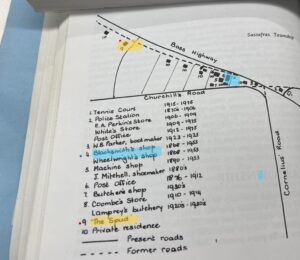

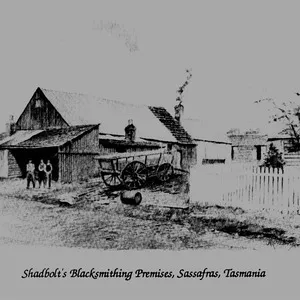

Shadbolts of Sassafras

Driving through the lush and productive farms of the Sassafras district on the North West Coast of Tasmania, it is hard to imagine they were once covered with an immense rainforest cleared using 19th-century machinery and tools. Before completing this research, I was not aware that my great-great-grandparents, George and Jane Shadbolt, ran a blacksmith and wheelwright business that supplied and maintained the equipment.

Their workshops were just along the road from the current Big Spud tourist attraction. I often refuel my car in Sassafras and tend to get lost in my own thoughts, trying to imagine what it would have been like when they first arrived. If you are a descendant of George and Jane, I suspect you will never think of Sassafras the same after reading their story. From a serial thief and lady of the night to pillars of the community, it was a stunning transformation. Not only astute businesspeople, but they were also intimately involved in the developing Sassafras community. There was no time to dwell on the past.

Formal Introduction

The Shadbolts of Sassafras exemplify the pioneering stories that Tasmanians cherish. Their tale is one of transforming impenetrable forests into world-class farms and raising families within a God-fearing community. These stories are often told as if time began with the pioneers, on land falsely assumed to be Terra Nullius, with their various pasts ignored or forgotten. The Shadbolt story is no different, but we do have insights into how and why their pasts were forgotten. Their conversion to Methodism, one of the most successful religious movements in colonial Tasmania, was so complete that their children and grandchildren had little inkling of their convict past. Further I suspect George made no mention of his wife and children he was wrenched from when he was transported. By 1860, the Black War was simply not discussed. For the Shadbolts, time began anew in the late 1850s, marking a fresh start. It is only from the safety of four or more generations of separation that we are now prepared to explore and accept their backstories.

For the first five years of their married life, the Shadbolts lived around the Cressy area. George, now with well-honed and sought-after skills, had little trouble finding work. He was listed as a carpenter on their marriage certificate and as a wheelwright on the birth certificate of their first child, Elizabeth Jane (my great grandmother), in 1859. In 1856, George was accepted onto the electoral roll as they leased land from Mr. James George Parker of Parknook estate, a property just south of Cressy. George became civically minded, engaging in local politics. Not only did he exercise his right to vote, but he also co-nominated William Pritchford Weston to run for the first House of Assembly election in 1856. I have no doubt Jane would have liked to vote as well, but women’s suffrage was still fifty years in the future.

The Shadbolts were living a pious, born-again lifestyle and were active in the community. However, shedding the convict stain was challenging in the class-riddled society of Northern Midlands, Tasmania, in the late 1850s. Additionally, the Shadbolts desired land, but it was increasingly difficult to acquire. Most prime agricultural land on the eastern side of the island had either been granted or purchased, with ownership concentrated among a relatively small group of the landed gentry. Further his cousin Benjamin’s convictions for stealing and resultant stints at Port Arthur were not helping Georges’s standing in the community. Fortunately for the Shadbolts, land on the North West Coast of Tasmania became available, and they saw an opportunity. In late 1859, they moved to become tenant farmers on 100 acres of Richard Uniacke’s much larger property of 640 acres at Sassafras. One wonders if they had any idea of what they were getting into, moving from open grasslands to an almost impenetrable rainforest.

The Port Sorell area had been settled by white people starting around 1830, but Sassafras was left untouched. The Shadbolts, along with the Sykes, Lampreys, Shaws, Beveridges, Ewingtons, and Rockcliffs, were among the first white settlers in Sassafras, arriving in the late 1850s. They described the Sassafras area as cold, damp, and forbidding, with huge trees standing erect like a phalanx of warriors that seemed to say, “Hitherto, man, thou shalt come, but no further.”. Tracks went to the left, right, front, and back of it, but not through it. Some thought it best to be left in its primeval solitude. It was not a place for man or beast; it was what we now know as climax cool temperate rainforest, a Gondwana forest. And just getting there was enough to deter all but the most adventurous and capable.

Journey to Sassafras

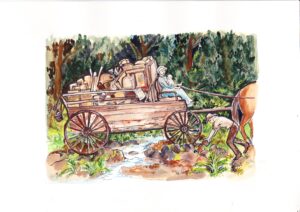

The Shadbolt family, consisting of George, aged 38, Jane, aged 28, baby Elizabeth, and their 8-year-old nephew Linden, embarked on a journey to Sassafras with all their worldly possessions. Their route took them through Deloraine, with the road from Cressy to Deloraine being well-developed. However, the track from Deloraine to Sassafras was known as the ‘missing link,’ shaded by immense rainforest.

This part of the journey was fraught with challenges, including negotiating fallen trees and mud holes large enough to dangerously bog a horse. They had to unload their carriage, carry their equipment around obstacles, and push the buggy through the bogs. From the comfort of the 21st century, their endeavour might seem foolhardy, but to them, it was a quest for freedom from a class-riddled society and an opportunity to build their own future.

Where modern eyes might see hardship, the Shadbolts saw opportunity. Where insurmountable challenges appeared, they saw problems to be solved. Having survived the worst of the convict system and guided by their newfound Christian beliefs, a little rain, mud, and a few big trees were not going to stop them. Eventually, they reached their selection in the Sassafras rainforest.

Getting Started

The Shadbolt’s first shelter was made from green saplings forming a frame, with cut ti-tree forming a skillion for the roof. They used bark to cover the walls and roof and a rudimentary fireplace was placed at one end. The family cooked, ate, and slept in little more than a smoke-filled shelter. As a matter of urgency, they built a more permanent wooden structure consisting of paling walls and shingle roof. Even the outside of the rock fireplace was clad with timber. The inside of the hut/house was lined with hessian and newspapers, providing a semblance of insulation.

The Shadbolts also started clearing their block to grow vegetables and raise animals. This involved ring barking the largest trees and clearing between trees by hand. Ring barking allowed light to get to the ground after the covering green canopy died. They used horse and bullock teams to do the heavy lifting. The Shadbolts soon learnt ring barking made falling limbs and trees in stormy weather a constant danger. One of Georges horses was killed by a falling tree in 18XX Clearing the land then was dangerous time-consuming work that would go for generations. The Shadbolts found soil of immense richness capable of growing high producing crops of potatoes, wheat, barley, oats and marigold. And the Shadbolts were entrepreneurial and began to see opportunities.

The 1850’s Gold Rush in Victoria was also fortuitous for the Shadbolts as it generated a huge demand for Tasmanian timber. Many small sawmills were built and boatload after boatload of the best construction timber was sent to Victoria generating a much need cash flow for farmers. Millions of tonnes of timber however, not suitable for milling were heaped up, using bullock teams and horses, and burnt. There were many incidents of fires getting out of control escaped into nearby ringbarked forest. There are recorded instances of children being killed on their way to school because of falling branches. While mindful of the dangers George seizes an opportunity.

The skills George developed by working as a carpenter, wheelwright, and blacksmith, while in convict work gangs and on assignment at the Dixon property proved invaluable. He was in the right place at the right time. In less than a year after his arrival George had set up a blacksmith and wheelwright business on the Uniacke property. This was the start of a successful business career and placed them in the hub of Sassafras social activity.

A fortuitous meeting with George Rockcliff, a free settler and devout Methodist, further integrated the Shadbolts into the community. Church services were held in the Rockcliff home, and despite a minor incident where a fire set by George Shadbolt burned down Rockcliff’s fence, their relationship remained strong. Together, they worked on essential projects like the road line between Sassafras and Latrobe, crucial for transporting supplies from the port at Torquay. The Shadbolts needed a reliable supply route to support their blacksmiths business.

Given the absence of any mention of Jane in local papers or historical reports suggests she was at least accepting of George and Methodism in this fiercely patriarchal society. While George was clearing the land and blacksmithing Jane was cooking, cleaning, and looking after Elizabeth Jane , Linden and George in the most basic of conditions. Washing boards, smokey open fires, cold and damp buildings, outside toilets and lack of running water come to mind. Jane worked somewhere between 10 and 14 hours per day every day including Sunday. Although in retrospect it appears hard and miserable, I doubt she saw it that way when compared to her previous life. Through her eyes she was free.

Great, great, grandmother Jane was a social being, so it was fortuitous the Uniacke property was near what was to become the central hub of the Sassafras community. Within a 2km radius of where she lived, a church, a school and retail businesses developed soon after the Shadbolts arrived, and they were part of the action.

1860 -1875

The Shadbolt’s conversion to Methodism not only taught them ‘to open their hearts in public forums’ it taught them to manage and organise meetings allowing them to be active community participants. Blacksmith’s shops were a focal point of pioneering communities with tools and equipment continually being dropped off and picked up, and people were coming and going. In the early 1860s Wesleyan church services were held in the Shadbolt’s blacksmith shop and in the home of Jonathon Graham’s house. Jane was then busy with her family and within the community. Jane‘s life though, was about to get busier, she fell pregnant in autumn 1862 and George junior was born in December. Unfortunately, he died at just fourteen months in April 1864. While childhood deaths were not unusual for the times it was a difficult time for Jane and George. By now, they were well-known and accepted within the Wesleyan community hence they would have been supported during this difficult time.

George was unable to read and write at the time of his marriage and it is not clear if Methodism went so far as to help adults learn these skills. However, George had become civic minded and very active on community groups. He actively participated in meetings and made representations to Government agencies. In 1865, he represented the newly formed school committee, advocating for a school to be built in the ‘Sassafras scrub near the Mersey’.

It seems though George also in the eyes of some became a little self opiniated. In December 1867 Edward Monkitrick took offence at George claiming he was the origin of the proposed new school and refuted George’s claims by writing to the Cornwall Chronicle. But he went further claiming the likes of George only wanted a school for the narrow minded few like himself and that George would like to see all religions prosper but the Roman Catholic.

George was undeterred and continued to be active at community meetings proposing, seconding, and supporting motions on the unfairness of tax laws, decadence of the community, a possible union with Victoria and the setting up of a committee to watch and report on legislation going through Parliament. George had become a vocal member of the community clearly embracing Wesleyan ideals. It is not clear if Jane became as unyielding in her beliefs as George. Whatever, their children were experiencing a fundamentally different childhood than if they were born to Jane and George in England.

Between 1865 and 1875 George’s business interests continued to expand. While working as a tenant farmer for Uniacke gave George a great start, he wanted his own land and over the course of the next few years bought three properties within a 3km radius of the Sassafras township. Linden, who was now in his early twenties and had been tutored by George for some time, effectively took over the blacksmith shop in the early 1870’s.

By 1875 George was a farmer, blacksmith, wheelwright, builder, and active member of the Methodist Church.

In 1865, Henry Rockcliff built a church accessible to preachers from all Christian denominations. In the early 1870s, the Methodists requested exclusive use of the church, but Henry refused.

Consequently, the Methodists set about building their own church, with services held in private residences, including the Shadbolt blacksmith shop, until the church was built. George, along with Reverend Brown, George, Francis and Jonathon Rockcliff, Jonathon Graham, Joseph Rawson, Benjamin Sykes, and Thomas Cutts, were the first trustees of the church. It was built in 1875-76, with the official opening on August 26, 1876. The church cost $400 to build, with much of the material and labour donated. George was appointed the first superintendent of the church’s Sunday school.

1875-1880

In the early 1870s, George’s life seemed to be flourishing. His businesses were expanding, he had a large house, children, and was a respected member of the Methodist community. However, his world came to a sudden halt on May 25, 1875, when his wife Jane died at the age of 43 from obstipation of the bowel. A painful and sad end for my feisty great, great grandmother. Her funeral was well attended by friends and the local community, and the Methodist community rallied around George, who now had five daughters to care for. Elizabeth Jane, who was 16 at the time, likely took on the responsibility of running the household and caring for her younger sisters.

Adding to George’s troubles, his nephew Linden, who was 23, married Rebecca King just four months after Jane’s death and they left for New Zealand to reconnect with Linden’s father, Benjamin. Linden had been running the blacksmith’s shop, and without him, George struggled to maintain the business. He advertised the business and associated house for sale in February 1876, but there were no takers, compounding his problems.

George developed a relationship with Elizabeth Turner, aged 33, 23 years his junior and they marry on 9th June 1877. Replacing Jane and becoming a stepmother to five children one of whom was already 17 and living with George who seemed to be becoming more rigid in his views was indeed a difficult challenge.

There was some good news in 1878 when Linden returned from New Zealand and set up a blacksmith business in ‘his old shop’. Linden had some success in New Zealand running the Heading of the Bay Shoeing Forge, a general blacksmith and wheelwright business, Family legend suggests however, all was not well between father and son. Recalling Benjamin owned hotels, a horse racing business and was involved in various schemes that were mostly within the law it must have been a challenge for Linden who was brought up in a strict Methodist community where drinking, smoking, and gambling were forbidden. The New Zealand Shadbolts thought the Tasmanian Shadbolts were sanctimonious wowsers. Oh dear! Whatever Linden takes over George’s blacksmith business which must have been a relief for George.

Some respite but George’s new marriage had problems from the start and only lasted three years. In 1880 Elizabeth leaves and George advertises he will no longer be responsible for any debts incurred by his wife as she has left the home without due cause. Further in 1880 Elizabeth Jane married Joseph Ewington, my great grandparents, meaning Elizabeth Jane left home. I am sure Elizabeth Jane married with her father’s blessing, but George was dealing one major family event after another as well as caring for four daughters and running three farms. Around 1880 he starts selling his farms. For the time George was becoming an old man and is starting to wind down. He died in 1882 aged about sixty from debility. He became frail and weak with some underlying but undiagnosable condition for the time.

I am a little biased, but the Shadbolts of Sassafras is a great story. They endured the sheer brutality of the convict system and then built successful businesses in the middle of a rainforest. This story alone is compelling, but their commitment to developing the local community makes it a great story. I am in awe of their resilience and their ability to navigate life’s highs and lows.