Ann’s Story -John Simmonds

A view from Blackfriars Bridge, London, along the Thames towards London Bridge. I vividly remember sitting in the café on the bridge, gazing at the Shard, the tallest building in London, with my daughter and her school friend from Tasmania. Both worked in London at the time. As I sipped my skinny milk latte with just half a sugar, trying to keep up with their lively conversation I thought how good is this, Vandemonians are recolonising. After a while, however not being able to keep up with the speed of the conversation, I found myself drifting back a couple of hundred years to the plight of John Simmonds, who walked down nearby streets to Blackfriars Wharf. He would not have been concerned about whether he had half or full sugar in his coffee.

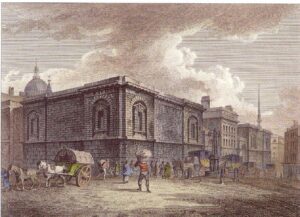

The next day, I decided to walk from Blackfriars Wharf to the Old Bailey, where Simmonds, a highwayman, was tried and convicted. As I neared the Old Bailey, I asked a police officer if he could show me the site of the notorious Newgate Prison where Simmonds was initially sent. With a rather wry smile, he said, “Right here,” and showed me a plaque about the prison. My accent gave me away; I was clearly just another in a long line of Australians making this pilgrimage.

Formal Introduction

A very old resident of Tasmania passed away at Sheffield on Saturday in the person of the late Mrs J J Ewington, who was nearly 82 years old and was born in Launceston. The deceased had 12 children (10 of whom are still living), 77 grandchildren, and 78 great-grandchildren to represent the deceased, who was well acquainted with the early history of Launceston.

My great, great grandmother matured with the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. Ann Ewington (nee Keep, nee Simmons), was born circa 1820, lived in and around Launceston for the first 16 years of her life, and observed and was impacted by some of the most dramatic events in Tasmania’s colonial history.

Ann’s parentage remains clear, her origins less so. Her life story captures a tantalising tale with two competing interpretations illustrating there is not a single colonial narrative, so much as competing Tasmanian narratives. Was she really adopted, or is she a projection of wishful family history-making?

One narrative has wide appeal, the other, for some, is still a step too far. Regrettably, it can become a polarising and acrimonious debate. On the one hand, she appears to be a stereotypical ‘settler’ child. Musters and death notices help build a plausible story that John and Catherine Simmonds really were Ann’s birth parents. Unfortunately, neither birth or baptism records exist which would nail down Ann’s story. She remains ambiguous.

The competing narrative to this ‘settler’ vision relies on anecdotes handed down through multiple branches of Ann’s large sprawling family. Have they survived for nearly two hundred years? If so, they suggest Ann was taken in by the Simmonds’s around 1820. In this version, they are not her birth parents.

Yet still, plumbing the back stories of John Simmons and Catherine Tobin gives useful insights as to why there are competing narratives about Ann’s birth parents. Simmonds’s story is a tale of hardship but adventure who on balance had a better and most likely a longer life in Van Diemen’s Land than if he remained in England. Tobin’s story however is one of abject poverty, neglect and cruelty without any hint of positivity. Unfortunately, it was the plight of many female convicts of the time.

John Simmonds England

John Simmonds 5’5’’ tall, green eyes, dark brown hair, and a sallow complexion was likely born at Reading, a small town about 40 kms east of central London circa 1770. Little is known of his early life, but we can safely assume he came from England’s underclass and was involved in petty crime from an early age. Aged about 21, in December 1792 he was convicted of assault and demanding money from a Mr Barlow at Holborn. He was sentenced to seven years transportation to New South Wales. After spending four months at the notorious Newgate Prison and nearly four years on the prison hulk Prudentia Simmonds was sent to New South Wales on the Ganges in 1797.

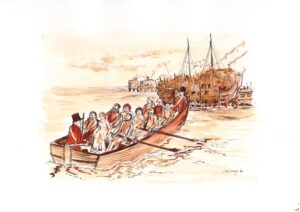

Now Simmonds may have been relieved to get out of Newgate. A trip down the Thames albeit in chains from Blackfriars wharf to the Woolwich Dockyard was at least a change in scenery. I wonder if he thought ‘surely the hulks cannot be any worse than Newgate’. They were.

Hygiene on the hulks was so poor, outbreaks of disease like typhoid and cholera were common. Disease spread quickly and the death rate among prisoners was high.

Magistrates observed inmates seldom reformed after being on the Hulks, or ever returned to honest industry. In their view the indiscriminate mixture of criminals rendered the Hulks a complete seminary of vice and wickedness. Simmonds somehow survived for four long years on the Prudentia so he must have been resilient and cunning enough to deal with the rough and tumble of Hulk life. In November 1796, Simmons was deemed fit enough to be transported He was moved from the Prudentia to Portsmouth in preparation to board the prison ship, Ganges, headed for New South Wales.

The Ganges

Unbeknown to Simmonds he was lucky. He sailed on the Ganges not the infamous Britannia the only other convict ship to arrive to New South Wales in 1797. Both ships were in Portsmouth Harbour in October 1797 being made ready to sail to Botany Bay. Convict ships of the time were overcrowded, unsanitary and often captained by merciless tyrants who also captained slave ships. Little attention was paid to the condition of convicts during the voyage. Conditions on the Britannia, captained by the sadistic Thomas Dennot, were so brutal and inhumane there was an attempted mutiny on the way to Botany Bay. The mutiny failed. Convicts arrived in Sydney in a sickly and emaciated state as a result of the punishment they endured because of the attempted mutiny.

The Ganges sailed on December the 10th 1796 just after the Britannia and arrived on June 2nd, 1797 six days after the Britannia. Begrudgingly Captain Patrickson, master and owner of the Ganges accepted 200 convicts to be boarded, 100 less than the 300 he requested. Luckily for Simmonds the Ganges was the first ship to be inspected by Surgeon General Fitzpatrick. As a result, ventilators and water purifiers were installed on the Ganges. Further fumigants and medicines were made available for use by the ship’s surgeon, James Mileham. Still 13 died on the trip. Simmonds and fellow surviving convicts arrived in reasonable health although some had scurvy. Simmonds then, survived a long challenging trip and fortunately he was not on the Britannia.

Sydney New South Wales

Simmonds, now about 26, arrived at Sydney a far-flung and not particularly important colony of the British Empire as a convict with few rights. It must have been a culture shock. Strange land, climate, plants, animals for a start. And if he thought these strange then the currency was rum. For some Sydney was a place of dread with public hangings and floggings used to instil fear into the colony. Bizarrely, although not uncommon for the times, they were spectator sports with people jostling for the best position to watch. I doubt Simmonds was a victim of this brutality but may well have been a spectator. Simmonds also found Sydney a place of opportunity, adventure, and a better way of life. Convicts could legally become property owners , shop keepers, publicans, and householders. Illegally they became distillers and ran brothels. Simmonds saw ex-convicts could become police constables and worked in conjunction with soldiers. He observed Aboriginal people around the streets of Sydney who were still trying to use their land. There is little doubt he met and interacted with Aboriginal people and was aware of the war on the Hawkesbury River. How the highwayman from London initially coped is not known but my hunch is he saw opportunity not dread.

Simmonds then was assigned to a landowner, businessperson or officer for the two years left of his seven-year sentence before applying for a Ticket of Leave. His supervisor may have been understanding and benevolent or a tyrant. Both existed. On balance, he did okay, as he obtained a Ticket of Leave and by 1805 became a sealer in Bass Strait.

Sealer of Bass Strait – Policeman in Launceston

Simmonds worked for Underwood and Kable, emancipists who became major players in the burgeoning seal industry. Up to a third of the ships, arriving at Sydney in the early 1800’s, were involved in either sealing or whaling. The industry provided much needed employment for convicts, like Simmons, who had served their time, were considered of good character and free from debt. Kable considered Simmonds fitted the bill. Simmonds sailed on his ships Marcia and Fox from Port Jackson to work on the Bass Strait Islands until at least 1808. For the first time in his life Simmons, about 34, was in paid employment.

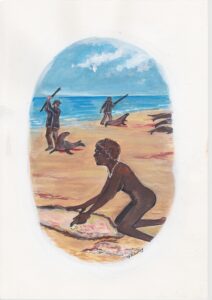

By 1806 almost 200 000 seals had been harvested but the rate of harvesting seals could not be sustained and by 1809 the industry collapsed. Large companies moved on but some sealers, including Simmonds, were attracted to the lifestyle, as harsh as it was and tried to ek out a living on the Islands. For the time, Bass Strait Islands were so remote the sealers were effectively living beyond the law with little or no government oversight from Sydney or the fledgling colonies of Hobart and Port Dalrymple. Initially this was the attraction free and living in a state of independence they never experienced before. The islands could not however provide all their needs and from 1810 sealers started visiting the north coast of Van Diemen’s Land. Meetings/clashes with Aboriginal people were inevitable.

How Simmonds was involved we can only guess, but he was there, and was a recognised sealer of Bass Strait. Further it is unclear how long he lived on the Islands, but we can safely assume he had many interactions with Aboriginal people. He was part of a Creole society that evolved with sealers taking on many of the ways of Aboriginal people to survive. After some time as a sealer Simmonds, now in his early forties sort a slightly more ordered and predictable lifestyle. Simmonds moved to the outpost of Launceston and became a policeman.

Policeman of Launceston

Simmonds was one of 27 policemen working under the direction of senior constable Thomas Massey servicing the County of Cornwall. It is unclear when and how he was selected by Massey but in 1816 he was listed as the designated officer at Massey’s farm. It was a part time occupation for Simmonds for which there was no monetary reward, but he was victualled from Government stores and allocated 1 pint of rum per week. His main task was to check on convicts assigned to settlers and keep senior constable Massey informed of local intelligence/gossip. Little was recorded as Massey was not allocated enough paper.

Now Massey was also responsible for musters but because of bad eyesight he often delegated the task to officers. Musters where Government inventories of people, both convict and free, property and livestock that enabled infrastructure planning and to ensure appropriate victualing. Recalling Simmonds could neither read nor write explains why musters were not always taken, were sometimes inaccurate, particularly in remote locations and they were often ad hoc. On balance, however, Simmonds would have been aware of the intelligence and gossip of the area, he most likely drank with convicts at night.

By 1820 Simmonds had lived for at least 15 years in an around Launceston and the North-East of Van Diemen’s Land. He was well acquainted with the area, had networks across the whole community and had some standing in the community. He was living on a block on the Esplanade bordering the North Esk river, east of a canal built near the confluence of the North and South Esk rivers. Simmonds then a rough bloke from London rolled with blows of life on the Hulks, dealt with the rough and tumble of Sydney, lived for a time on the fringes of the British Empire in Bass Strait and then moved to a slightly more settled existence in the frontier town of Launceston. And he wanted a wife