Ann’s Story -Catherine Tobin

Catherine Tobin’s name appears in Philip Tardif’s book, Notorious Strumpets and Dangerous Girls: Convict Women in Van Diemen’s Land. While the title may seem harsh, it is important to remember that many of these women, including Tobin, were simply trying to survive against overwhelming odds.

In the late 1820s, the streets of Launceston were no stranger to Tobin’s alcohol-fueled rages. Had I encountered her during one of these episodes, I would have likely kept my distance. However, as I delved deeper into her story, my initial judgment gave way to sympathy. Unlike the other main characters whose stories ended on a positive note, Tobin’s tale is one of hardship and misfortune. Her story is not for the faint hearted.

Formal Introduction

I find Catherine Tobin’s story disturbing on multiple levels. I am amazed she survived for so long. If this is part of the stain Tasmanians try to forget, then maybe we should but that would be cowardly. It is a story of abject poverty, neglect, and brutality and gives an insight into racism and sexism of the early 19th century. Unfortunately, many convict women endured similar abuse.

Tobin born c1787, at Skiboreen a small town near Cork Ireland, was illiterate, lived-in poverty and was a huckster on the streets of Cork, Ireland. In 1817 she was tried for selling stolen muslin, found guilty and sentenced to 7 years transportation to New South Wales. A life sentence as she had little hope of ever seeing her homeland again. She spent 5 months in a Cork jail before being transported along with 88 other females to Port Jackson onboard the convict ship Canada.

So as with Simmonds Tobin had a little luck. All 89 convicts survived the trip to Sydney arriving early August 1817. The ship’s surgeon reported to Governor Macquarie that all convicts and children were in good health and to the best of his knowledge no female had lived with a sailor and prostitution had not taken place. H’m not sure about that it was a matter of survival.

Tobin was sent to Hobart from Sydney on the Elizabeth Henrietta on August 11, just five days after arriving in Sydney. On arrival, Governor Sorrel ordered Tobin and fellow female convicts be sent onboard the brig Governor Macquarie to Port Dalrymple to help correct the imbalance between males and females.

Launceston 1817 -1820 Catherine’s new ‘home’

Sorrel replaced the incompetent, drunken but hamstrung Davey as Governor of Van Diemen’s Land early 1817 just before Tobin arrived. Davey had almost lost control of the colony. The infamous bushranger Michael Howe challenged him as an alternate governor. Law and order were ad hoc to say the least. A government surveyor and the assistant commissioner stationed at George Town became bushrangers after refusing to pay some debts. The 150 or so houses in Launceston were little more than hovels that started as lean–tos and gradually improved. People often wore clothing made of animal skins, as clothing was in short supply. There was a large imbalance between men and women , at times as high as 9:1. Violence towards women was widespread in all of Van Diemen’s Land. Women needed a protector to survive. Now for Tobin the landscapes, buildings and animals was disconcerting enough but what happened on arrival must have been a shock.

John Simmons and Catherine Tobin become a couple.

On arrival at Port Dalrymple Catherine Tobin was available for selection by a settler straight from the ship or she would have been victualled from Government stores cohabited with a male convict. There was no government facility for processing. The gaol in Launceston was little more than a hut, only partially roofed with a dirt floor. Often prisoners could only be restrained by chaining them to the wall. Further the use of steel collars and stocks were common forms of punishment for female convicts. Maybe Tobin was better off to be just selected but it was still brutal. So, after 4 months at sea, on three separate ships Tobin was then available to become someone’s ‘wife’.

Remembering John Simmons, a policeman, was well established in Launceston may have selected Tobin from the ship or taken up with her soon after. It was not unusual for a female to be selected but not even make it to her new home before another male of higher standing moved in. Whatever they lived as a couple in Simmonds’s house/hut on the Esplanade, Launceston, next to the Reibys who ran a shipping business just along from a recently built canal. So, Tobin an Irish women from Cork, aged about 30 was coerced to live with Simmons a man from northern London , aged about 45 in a hut cobbled together from whatever material was available. Most likely it had a dirt floor with a smoky fire at one end. Launceston was at the edge of the frontier, and it was a violent dangerous place for women.

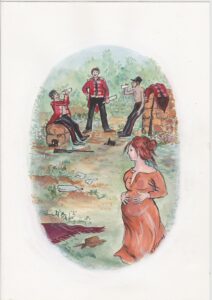

A Disgraceful Event

As difficult as Tobin’s new circumstances were, they became much worse. Unfortunately, not even Simmonds, a policeman or ex-policeman, could protect Catherine Tobin on the 5th of May 1820. Mary Nesbitt, who was transported on the Canada with Tobin, was raped by four soldiers near Reiby’s Paling. Tobin eight months pregnant, with Simmons’s child, heard Nesbitt scream for help and went to her aid. She was of no help. The soldiers assaulted Tobin as well. They knocked her over, kicked her in the stomach and raped her.

Simmonds heard cries for help and observed men coming from Reiby’s Paling and went to the women’s aid. . He pleaded ‘that his wife was in no state to be ill-used’, but the soldiers just turned on him as well. Simmons was injured so badly he could not get out of bed for eight days. During the incident, the soldiers told Simmonns ‘they will do what they like and will serve every convict bitch the same way’. Nearby soldiers finally arrested the offenders, and they were sent for trial at George Town. Launceston was a terrifying place for the likes of Tobin.

The baby, named Thomas, did not survive and was either still born or died shortly after birth with bruises and indentations on his head caused by the assault. The death certificate listed Catherine Tobin and John Simmons (Symons) as parents. Apart from Simmons, Tobin had only her friends, like Nesbitt, as support. There was little medical and certainly no counselling or psychological support to help her through this trauma. She would never recover but just six months later she married Simmons on January 1st 1821.

Later in 1821 a daughter Ann, aged about two, was listed on a muster associated with John and Ann Simmons. There are competing views however, as to whether John and Catherine Simmons are Ann’s birth parents.

.

Genealogy of the Simmonds Family

There were three children associated with John and Catherine Simmonds. Thomas above, and two females Ann and Elizabeth. The genealogy of Elizabeth is clear. She was born in 1823 although the birth and baptism was registered in 1826 and she married in 1840. For Ann it is a muddle to say the least as we only have muster evidence and recalling they were not always reliable and some muster records have been lost.

Birth or baptism records for Ann have not been found. She was listed on an 1821 muster, an infant, aged about 2, associated with John and Catherine Simmons (Tobin). She was listed on an 1827 muster of children with both parents living, aged 7, could not read or write and of indifferent character. John Simmonds and Catherine Tobin are listed on the 1818 muster, but no child associated with them was listed Catherine Tobin while a convict was not listed on stores. The 1819 muster, records John Simmonds, from the Ganges, with another person associated with him, but it is not clear who. No child of an appropriate age or name was listed. If the 1820, 1821 and 1827 entries are accurate Ann cannot be born to Catherine Simmonds, nee Tobin, as baby Thomas died at about four weeks in June 1820. I acknowledge caution need be exercised with my summary as it relies on muster information and recalling they were not always accurate. If there were no competing stories, then given the vagaries of musters at the time, a case can be made that John Simmons and Catherine Tobin are the birth parents of Ann. Many accept this interpretation. But there are competing stories.

Stories from across this large Tasmanian family

Whilst doing the background genealogical research, I have encountered at least six people from across my large extended family, who do not know one another, who believe they were bought up in an Aboriginal family or family stories mention Aboriginal people or dark people somewhere ‘way back’. I vividly recall talking to one of my aged relatives about my research and mentioning possible sealer and Aboriginal connections. She said, ‘Oh yes that’s right didn’t you know that … but we weren’t allowed to talk about that.’

Alan: Growing up in Circular Head in the seventies I was told my family was related to the Ewingtons and that we had Aboriginal cousins at Woolnorth. There were black grandmothers in my maternal grandfather’s family. But other than that it was not talked about.

Later in my professional life, I worked closely with the Aboriginal community and started researching my own ancestry.

My father was a Russian immigrant’s son from Queensland, which left only my Mothers side to investigate. I went into the archives and using the microfiche Colonial index traced her family. Every branch of the family led to a convict or an immigrant, except one; Ann Simmonds.

As I delved into the history from a European and Aboriginal perspective, I realized that I was not going to get the written proof I looked for. The events of that time are confronting and they were not accurately recorded. This journey for me has seen an evolution in my epistemology from my Physics and Philosophy training to understanding the Aboriginal connection to the country. I have moved on from trying to prove my identity. My mother shared with me a love of the coastline and collecting shells.

When after a series of coincidences a few years back on a weekend trip to Lake Barrington ,I was directed to the location of Ann’s grave. After an hour’s search, I found her broken headstone. Immediately I heard the call of two black cockatoos. I looked up immediately from the grave as the two birds touched wings. I have a close association with these birds and despite seeing them on a daily basis, this was they only time they touched wings. Community believes minungana black cockatoos are the messenger birds of the ancestors.

Growing up with the extended family of my mother’s two sisters, I have been able to

share the knowledge of our common ancestors although they know it more from their childhood stories.

When my aunty asked her father why he didn’t talk about their Aboriginal past he said he dare not for the fear of having his kids taken off him.

Stacey: All I know is that there was a lot of secrecy in the family about my Grandfather’s family history he said they were “French Canadians” especially when anyone suggested they were aboriginal. There were rumours they were aboriginal but I’m not sure where this came from.

The “French Canadians” were convicts from England transported in the 1840’s

Diane: There is a story that my great great grandmother came from the Tiwi Islands and that’s why some people look dark in the old photos. I am not sure if it is true, but it is what I have been told.

The great, great grandmother was born at Port Sorell, Tasmania, to parents who were convicts arriving in the 1840’s.

Some stories are supported by photographs. Some families are active in the Aboriginal community. Independently family genealogists attempting the Ewington family story come up with the same question: Who were Ann Simmonds’s birth parents? In my view it is a distinct possibility her birth mother was Aboriginal. She was taken in by Catherine and John Simmonds in late 1820 or early 1821.

Lyndall Ryan indentified at least fifty Aboriginal children who were taken in by settlers and suggested there could have been more. Babies where just taken from their mothers and the mothers were left to mourn their loss. Robinson recorded Aboriginal women, who lived with Bass Strait sealers, left children in Launceston. Further children born to Aboriginal women fathered by white men were often shunned by both Aboriginal and white society. Now Simmonds was a sealer of Bass Strait, became a police officer around Launceston and had networks across the community. In my view John Simmonds with the help of others ‘found’ a baby to take the place of Thomas.

Some consider this a preposterous story but given the unimaginable trauma Catherine experienced losing baby Thomas, I consider it a definite possibility. You can make your own interpretation, but for me this research has brought into sharp focus there are competing and sometimes opposing views of our past. Stories about our convict heritage have become mainstream, almost dinner party conversation starters, with people claiming a convict ancestor almost as a badge of honour. Family stories that involve close involvement with the attempted genocide of the Van Diemen’s Land first people, however, still seem taboo.

Some years back I thought the origins of Ann’s birth parents could be solved with simple yet hopeful idea: a DNA test. Initially, the search seemed straightforward. I contacted two companies, seeking a test to help solve the riddle. The first company’s response, “We do not do this sort of work.” was at the time a little surprising. On reflection my initial thoughts were quite naïve.

The second company explained that without a direct line of females tracing back to Ann, the likelihood of obtaining useful information was slim. This led to a temporary halt in the investigation. More recently the sophistication of DNA testing improved significantly.

A recent breakthrough came when a person, having recently used one of the more popular DNA tests, contacted me. Her genetic profile revealed predictable matches with various regions of Great Britain. However, what stood out was a significant match with Australian Aboriginals. This unexpected result prompted an exhaustive genealogical investigation, ultimately revealing that great-great-grandmother Ann was the most likely source of this unique genetic material. I find this a compelling addition to the other stories.

The tantalising multiple interpretations of Ann’s story has forced me to deal with the Great Forgetting in a much more complex manner rather than trying to just prove one or other of the stories. But for me the weight of evidence suggests Ann had at least an Aboriginal mother, but I will leave it to the reader to make your own judgement. What follows, I hope, reflects the duality.