Ann’s Story -Childhood

.

I know very little about Great Great Grandmother Ann’s physical appearance, except she was short of stature, which doesn’t surprise me. In her old age, she sang a lot, which I find fascinating. She did not go to school and, as a child, could neither read nor write. At the tender age of seven, she was labeled as having an indifferent character, which, given all she achieved, seems quite perplexing. It disturbs me that a child could be labeled in such a way but they were harsh times.

Formal Introduction

….well acquainted with the early history of Launceston

In the early 1820s, Launceston was a remote and tumultuous frontier town, marked by violence and rapid development. Ann Simmonds, along with her parents John and Catherine, and her sister Elizabeth, lived in and around Launceston during these formative years. The town was expanding, taking over from George Town as the main center for government administration. Despite the lack of formal education, Ann grew increasingly aware of the town’s happenings.

By 1829, at the age of nine, Ann most likely witnessed the public hangings of convicted bushrangers and the frequent whippings of prisoners. Launceston was also experiencing prosperity with good harvests, a plentiful supply of meat, and abundant jobs. The town’s public and private buildings were improving, making it a place of opportunity for freewheeling entrepreneurs. Ann also sensed the growing hysteria in the town due to the Black War.

First Home

In the year 1821, the family resided in a modest house/hut adjacent to the Reibys on the Esplanade, which bordered the North Esk River. It was constructed from whatever materials were available at the time. It consisted of one or two rooms, with a fireplace at one end that served both for cooking and providing warmth. The toilet was located outside, and there was no connected water supply. Despite these rudimentary living conditions, the proximity to neighbors was likely a significant comfort for Catherine, especially considering the hardships she endured in 1820. Ann, being very young, would have no memory of their first house1

East Tamar- Farm

In 1822, John, a man in his late middle age, was granted 40 acres of land on the eastern side of the Tamar River, six kilometers from town. Although 40 acres was not a substantial amount of land, the Simmonds family managed to sustain themselves as subsistence farmers living in a makeshift house. By 1823, they owned 13 cattle and 14 hogs, allowing them to earn some money by selling produce in Launceston. It is possible that John supplemented their income with other work, given his background as an ex-policeman and his well-known status in the community.

But all was not well as Catherine Simmonds was frequently arrested for being drunk, disorderly, and fighting in the streets. No doubt this behaviour stemmed from the trauma of her transportation and ordeal in 1820.

Ann would also recall walking into town with her parents and her sister Elizabeth to sell produce and buy supplies. From a young age, she became familiar with the town. Although she may not have fully grasped the significant events occurring in Van Diemen’s Land between 1825 and 1835, she would have sensed the growing tension in the town. The white population of Van Diemen’s Land grew from 15,000 in 1825 to over 40,000 in 1835. Large landowners, who received free grants of land from Governor Sorrell or Arthur, cultivated and enclosed land with fences, introducing different plants and animals without regard for the Aboriginal people.

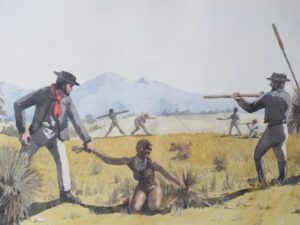

Many settlers were directly involved in or funded roving parties to remove Aboriginal people from their land. As a result, Aboriginal people were increasingly denied access to their ancestral homeland and began to fight back.

A Business Venture Goes Wrong

In 1827, John Simmonds was recognised as a farmer. However, in either 1827 or 1828, he ventured into business with George Burgess, a well-known wheeler and dealer in Launceston. Unfortunately, their business endeavor did not succeed, and Simmonds found himself indebted to Burgess for at least 300 pounds, a sum he could not repay. Consequently, Burgess took Simmonds to court, where Simmonds was ordered to pay Burgess the 300 pounds along with 66 shillings in court costs. This was an enormous amount of money for a small farmer like Simmonds. Unable to raise the funds, Burgess foreclosed on the Simmonds farm. A public dispute ensued, but Simmonds managed to retain the farm, though he was left in financial ruin.

During the same period, from December 1828 until October 1829, Catherine Simmonds was arrested on four occasions for being drunk and disorderly and fighting in the streets. On at least one occasion it was a public family brawl as she was fighting with John Simmonds. It is possible that Simmonds tried his hand as a licensee of one of Burgess’s hotels, giving them easy access to alcohol, which they could not handle. From the perspective of Ann and Elizabeth, their family life was in disarray, even by the standards of the 1820s and 1830s. The turmoil in their family life was mirrored by the uproar among the people of Launceston. As children, Ann and Elizabeth would have sensed the hysteria by listening to the talk of the town as they played on the streets of Launceston.

The Talk of the Town

In 1829, the town of Launceston was a place of stark contrasts and turbulent events. The local newspapers, such as the Cornwall Chronicle and Launceston Advertiser, often led with reports of the Black War, reflecting a biased white perspective. The white population was in a frenzy, overwhelmingly desiring to “get rid of” the Aboriginal people.

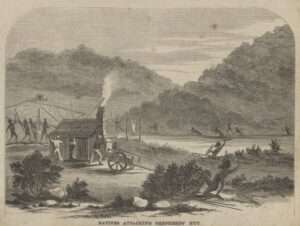

Close to the Simmonds farm, significant events were unfolding. On March 16, 1829, the Launceston Advertiser reported a raid on the Millar property by individuals initially thought to be Aboriginals. However, it was later revealed that the raiders were white men who had colored their faces black to frighten the house occupants before pillaging the house. This bizarre incident highlighted the strange and dangerous environment in which Ann lived.

In February 1829, a shepherd working for Mr. J.W. Bell was suddenly speared while tending sheep at Cummings Folly, about five miles from Launceston. Ann and Elizabeth may have witnessed a corporal and four men, under the command of Captain Donaldson, leaving the town in search of the Aboriginal attackers.

Further reports indicated that Boomer, a black native, was shot dead after striking a sergeant and attempting to escape. This incident was used to underscore the perceived unreliability of Aboriginal guides.

In the same edition, the Launceston Advertiser reported that the chief justice had passed the death penalty on 15 prisoners found guilty of various capital offenses, including rape, murder, and stealing with violence. The hangings took place shortly after, and other prisoners were sentenced to transportation, fined for petty theft, or flogged and released. It is possible that Ann observed these gruesome events, as public executions and floggings were common spectator sports in the 19th century.

Strangely, despite the violence and turmoil, the Launceston Advertiser also reported that the town was flourishing. Farms were progressing with fencing and cultivation, English grasses were plentiful, and staples like meat and bread were cheap and readily available. Labourers and mechanics were in high demand, and a beggar was rarely found. Compared to England, where many people were subsisting on poor rates, labourers in Cornwall were well-paid and provided with lodgings and board. However, the white population believed that all this progress was in jeopardy unless something was done about the Aboriginal people.

The Black War

In the late 1820s, the Aboriginal population in Van Diemen’s Land had been severely reduced, yet Aboriginal warriors continued their desperate fight to protect their land. By the end of 1829, Governor Arthur faced mounting pressure to take decisive action. This urgency was one of the reasons behind his visits to Launceston in 1830 and 1831. Ann heard the musket fire from the soldier’s barracks heralding the arrival of the Govenor. Even a child she would sense the drama of it all.

During his 1830 visit, Governor Arthur summoned various leaders to assess the town’s progress. He inspected roads and buildings, identifying areas for improvement as the town rapidly expanded.

Arthur also met with Batman to devise a strategy using Aboriginal women to persuade Aboriginal men to surrender, aiming to end the Black War.

Despite these efforts, the conflict escalated. Settlers pressured Governor Arthur to take more drastic measures, leading to the launch of a major military campaign in late 1830, known as the Black Line. This operation was the largest military endeavor on Australian soil since white contact in 1788, involving a total of 2,200 men, including 500 soldiers, 800 assigned convicts, 400 Ticket of Leave men, and 500 free settlers. These forces were organized into divisions, each with specific positions, and moved across the eastern half of the island to drive all remaining Aboriginals towards the Tasman Peninsula for capture and relocation to the Bass Strait Islands. However, the operation only resulted in the capture of two Aboriginals: an old man and a young boy.

Ann witnessed the northern division, led by Captain Donaldson, comprising 450 men, departing in late October 1830. Almost all able-bodied men, including soldiers, convicts, and free settlers, were mobilized. Donaldson’s division moved over the Central Highlands, meeting with southern divisions in a pincer movement. The town buzzed with activity and excitement, with mandatory toasting of the queen and other fanfare as the division prepared for what was considered a war effort.

There is no evidence that Ann’s father, John, who was in his late fifties and had been a policeman, was part of Donaldson’s division. He was more likely a member of the town guard, securing the town as most able-bodied men joined the Black Line. Regardless, Ann and her sister Elizabeth would have sensed the excitement in the town.

An interesting twist in this story, which Ann heard about but likely not fully understood, involved an Aboriginal leader and a small band of four men and one woman on the Central Plateau. They eluded capture by Donaldson’s division and stalked the soldiers until they slept, then speared two of them in retaliation for previous atrocities. Captain Donaldson, furious at being made to look foolish, ordered the band to be shot on sight. However, they were not caught and eventually joined George Augustus Robinson, the Aboriginal conciliator, near Anson’s Bay on the East Coast of the island on November 1, 1830.

End of War

The end of the Black War marked a tumultuous period in the history of Van Diemen’s Land. As members of the Black Line offensive returned to Launceston, they did not come back as triumphant heroes. Instead, they were bedraggled participants in an unsuccessful campaign. The streets of Launceston must have been filled with a mix of relief and fear, especially for families like Ann’s, who were still threatened by Aboriginal groups engaged in guerrilla warfare on the East Tamar.

Despite the Black Line’s failure to capture significant numbers, Aboriginal leaders realised the war could not be won by force. They sought to negotiate with Governor Arthur through Robinson, who consistently promised but delayed a meeting. It took nearly a year before Arthur finally agreed to meet in September 1831.

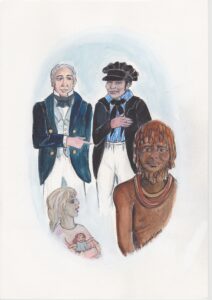

The Aboriginal group, Robinson persuaded to camp on Waterhouse Island to wait for the meeting with Arthur, walked through Launceston in early October. Ann may have witnessed this procession, and unbeknown to her close relatives may have been in the group.

After the meeting, Aboriginal people were persuaded by Robinson to relocate to Gun Carriage Island and then to Flinders Island on the agreement they could return to their homeland at a later date. The Black War came to an end. The mid-1830s were a time of relative calm and prosperity for white settlers but the relocated Aboriginal people faced misery and abuse at the Wybaleena settlement on Flinders Island.

The Simmonds’ family moved on. John seemed to be able to roll with the ups and downs of life but Catherine continued to find life difficult. Although Simmonds retained the farm until at least 1834 I doubt the family were living on it. More likely John called in favours through his previously developed networks as a policeman and finds work as a carpenter in the district of Morvern, about 10 kms south of Launceston.